WELCOME

CHRISTMAS!

THE KAFS YEAR SO FAR AND

OTHER YEARS...

THE NEW LONDON

MITHRAEUM

THE FIRST WINE NOW 6000

YEARS AGO

Dear Reader, we will be emailing a Newsletter

ALL THAT GLITTERS

each quarter to keep you up to date with news

and views on what is planned at the Kent

MOST WATCHED

DETECTORISTS

Archaeological Field School and what is

NEOLITHIC EXCITEMENT

happening on the larger stage of archaeology

both in this country and abroad. To become a

SPORTSMAN OF THE YEAR:

GAIUS APPULEIUS DIOCLES

member or subscribe to the newsletter go to the

THE MAN WHO CREATED

ROMAN BRITAIN

bottom right hand corner click where it says

THE ANGLO-SAXON FENLAND

‘Click Here’.

I hope you enjoy!

THE DARKENING AGE

Paul Wilkinson.

SCYTHIANS

ANGLO-SAXON BIBLE

BEOWULF IN KENT

CHRISTMAS IN KENT

THE KAFS EVENTS

Breaking News: Christmas!

COURSES FOR 2018

KAFS BOOKING FORM

It was a public holiday celebrated around December 25th in the family home. A time

KAFS MEMBERSHIP FORM

for feasting, goodwill, generosity to the poor, the exchange of gifts and the

decoration of trees. But it wasn’t Christmas. This was Saturnalia, the pagan Roman

winter solstice festival. But was Christmas, Western Christianity’s most popular

festival, derived from the pagan Saturnalia?

The first-century AD poet Gaius Valerius Catullus described Saturnalia as ‘the best

of times’: dress codes were relaxed, small gifts such as dolls, candles and caged

birds were exchanged.

Saturnalia saw the inversion of social roles. The wealthy were expected to pay the

month’s rent for those who couldn’t afford it, masters and slaves to swap clothes.

Family households threw dice to determine who would become the temporary

Saturnalian monarch. The poet Lucian (AD 120-180) has the Roman god Saturn say

in his poem, Saturnalia:

‘During my week the serious is barred: no business allowed. Drinking and being

drunk, noise and games of dice, appointing of kings and feasting of slaves, singing

naked, clapping

an occasional ducking of corked faces in icy water- such

are the functions over which I preside’.

Saturnalia grew in duration and moved to progressively later dates under the

Roman period. During the reign of the Emperor Augustus (63 BC-AD 14), it was a

two-day affair starting on December

17th. By the time Lucian described the

festivities, it was a seven-day event. Changes to the Roman calendar moved the

climax of Saturnalia to December 25th, around the time of the date of the winter

solstice.

BACK TO MENU

Breaking News/2:

The KAFS year so far and other years...

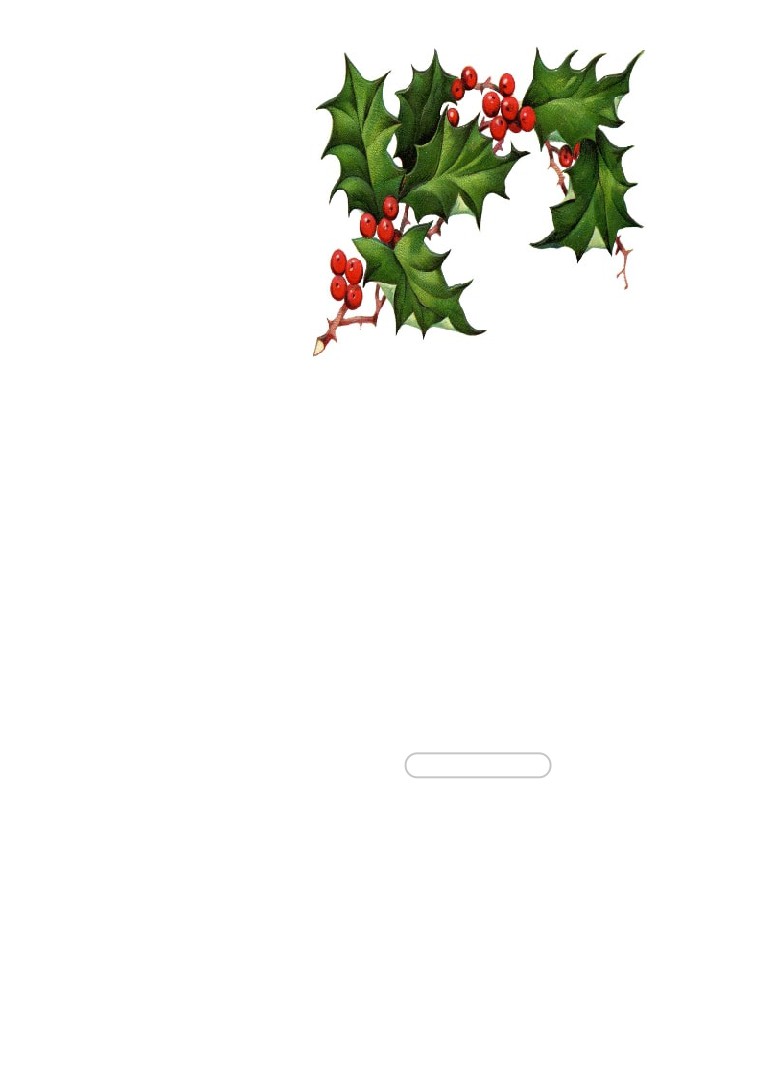

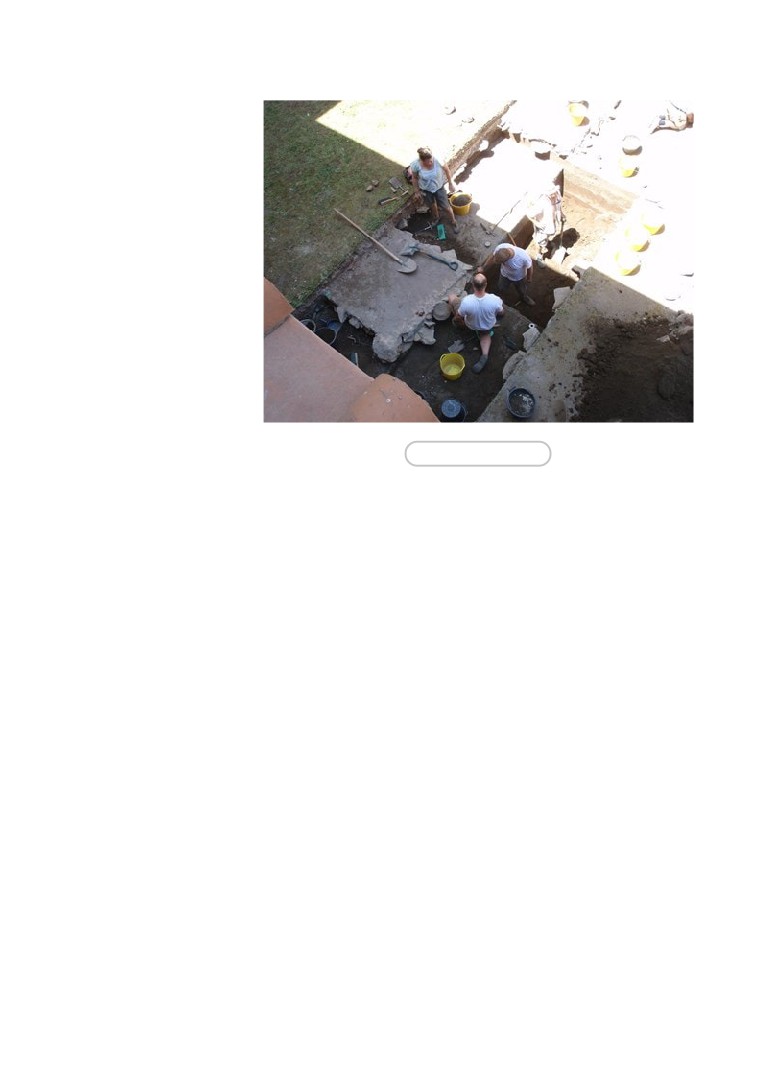

KAFS ‘dig’ at Star Hill near Bridge- can you name the diggers and the year? First

answer on a postcard wins a free course!

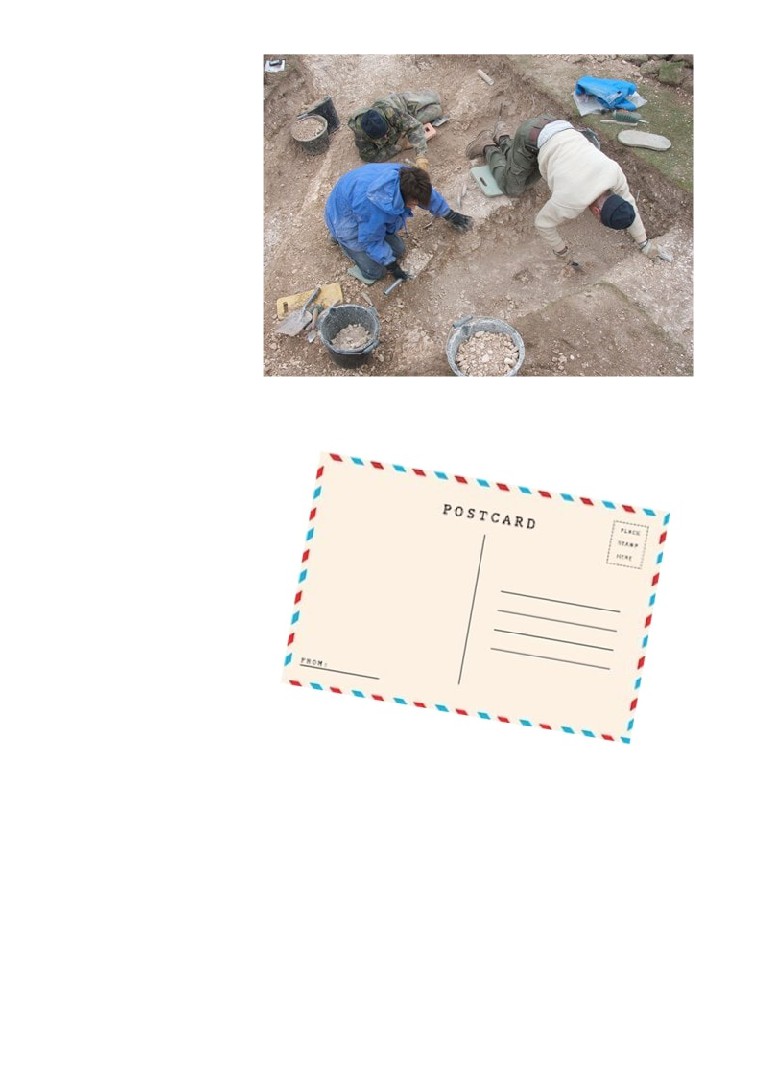

2017 at Abbey Barns, Faversham a spectacular year of discovery for the KAFS

archaeologists with additional investigation on the aisled barn at Abbey Fields in

Faversham and whilst other years work had focused on the bath house the building

this year’s work investigated the other end of the building with spectacular results.

We can now say the at the original 2nd century aisled building was built with

rectangular stone columns but unlike Hog Brook aisled barn the building at Abbey

Fields was extended in the 4th century with timber posts for another 85 Roman feet

(approx 25m) but on the same alignment and spacing as the original stone and brick

columned building.

Artist impression based on the earlier excavation results of the Roman aisled

building at Faversham but now with a 25m timber framed extension to be

added to the illustration.

Earlier work on the complex’s bathhouse has yielded prestigious small finds

including silver jewellery, exotic glass vessels and large quantities of coloured wall

plaster which, together with the structure’s stone and brick build of impressive

dimensions, measuring some 45m by 15m, suggests a building of some importance.

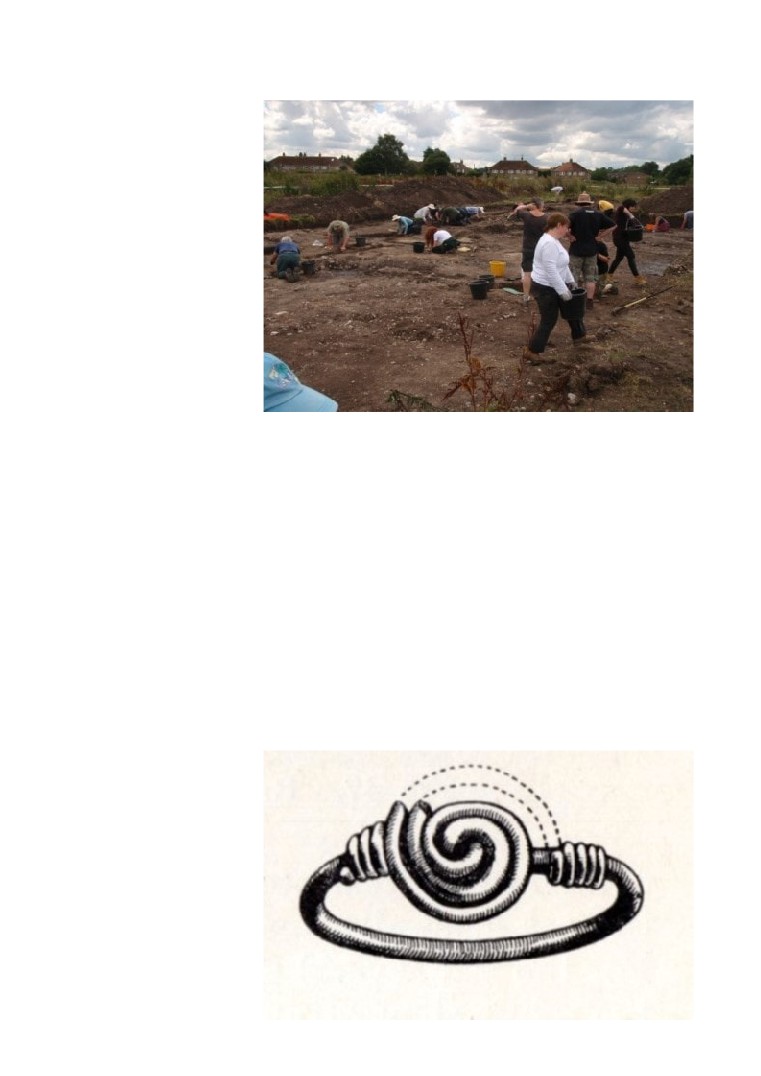

A silver finger ring (next page below right) found in the demolition rubble has been

dated to the Anglo-Saxon period and similar rings found at Dover have a date of c.

575-625 AD. The ring, only big enough for a child’s hand suggests the building was

demolished in the late 6th century to make a platform for a timber hall found in last

year’s excavation. Pottery in the cill beam slots dated this building also to the 6th

century.

Pottery sequence - The pottery sequence is also of particular importance with

Roman pottery starting from c.125 AD but the majority of surviving sherds - both

Late Roman and Early Saxon are from c.400 AD.

The pre-Late Roman element, and principally those of Early Roman date, consists

of both a few large fresh sherds and more worn material - including a few severely

abraded elements. The count of material that can be confidently allocated to the mid

third century AD is comparatively low, with most of the Mid Roman component

tending to be datable to between c.150-225 AD. Other than the noted variation in

sherd size and condition - and the presence of a few burnt sherds from Southern

and Central Gaulish samian vessels

- there is nothing particularly significant

amongst this material

- with most sherds stemming from kitchen wares and

individual sherds or sherd groups going through the normal range of discard

histories that excavation of a fairly long-lived occupation site will provide.

However, the bulk of the Late Roman pottery is different. With the exception of the

sherds from Contexts 101-2 and 105 all the Late Roman sherds are only slightly

worn or near-fresh. This latter condition applies to the Late Roman grog-tempered

sherds from Contexts 103-4, 110, 124, 126, 141-2, 201 and 205. Of these, the large

near-fresh lower-body sherd from 126 and the similarly basically unworn material

from 124 and 141, all suggest recovery from undisturbed contemporary layers or

features. Even those that are superficially ‘residual’ in other contexts are basically in

a similar condition - and generally unlike the majority of associated later sherds.

Admitted, the sherds from 101-2 and 105 are more obviously worn than the latter -

but this could be due to either original Late Roman post-abandonment exposure -

or just a degree of re-exposure during later post-Roman activity.

The over-riding feeling with all this material is that it stems directly from a near-final

phase of Late Roman occupation. ‘Near-final’ because of the possible evidence

from Context 142. This contained 2 near-fresh LR grog-tempered sherds but also a

fairly small rather worn crudely-made thick-walled dish base in a coarse-grained

quartz sand fabric. It has a quite high interior burnish and is fairly hard-fired with a

patchy skin of coarse sand - similar to its fabric’s - adhering to its underside.

Although its relative crudeness could suggest an Early, more probably, Mid Saxon

date - the fabric type is not really typical of regional Saxon fabric recipes. Initially, its

manufacturing characteristics all suggest a rather crude thickly-potted earlier fourth

century AD product

- perhaps not quite sub-Roman in type but superficially

suggesting that possibility.

Reviewing the current sherd evidence further - it is interesting to note that of the

recorded finewares traditionally mostly associated with the Late Roman period -

Nene Valley and Oxford colour-coated vessels - the Nene Valley ‘castor box’

bodysherd from Context 103 is severely abraded compared with the associated

grog-tempered sherds.

This might be no more than a bi-product of differing post-loss sherd histories but is

mentioned here to amplify another point. That is the different wear-pattern amongst

the purely grogged sherds from Context 141 which, amongst mostly near-fresh

material, includes one body sherd with fairly heavy unifacial wear and two other

lightly worn sherds.

Again this might be due to post-abandonment damage but it may also indicate the

type of wear normally acquired by discarded sherds during a moderately long period

of occupation. This point may be under-pinned by at least two sherds from the same

context - and a few more from other contexts - which have rather hard ringing

fabrics compared with the majority of lower-fired grogged sherds.

Pollard, in his quantified analysis of the Late Roman pottery from the Marlowe Car

Park, Canterbury excavations (Pollard 1984), made it clear that first - ‘scorched’ or

hard-fired wares tended to die out by c.350 AD and second - that the specifically

Late Roman type of grog-tempered pottery increased during the latter half of the

fourth century. This site has so far produced mostly rather low-fired grogged sherds,

with only low quantities of associated other sandy wares. Summarising, the

implications are that whilst some sherds may represent LR activity between c.275-

350 AD, the majority stem from an apparently increased c.350-400 AD phase of

occupation. Since the really crude lumpy grog-tempered products that technically

should epitomize the ‘decay’ period of c.400-425 AD (or from slightly earlier) are

absent, it is suggested that this phase of occupation is likely to have terminated

between c.375-400 AD or only very slightly later. Finally, it is tempting to suggest,

but does require further site and specialist confirmation, that the single crude coarse

sandy ware dish sherd from Context 142 may reflect late post-abandonment activity

between the period c.400-425 AD.

Abbey Barns Roman Villa: The class of 2017

BACK TO MENU

Breaking News/3: The new London Mithraeum

This is the first look inside an 1,800-year-old Roman temple that has been brought

back to life in London. The building, dedicated to the god Mithras, has been restored

to its original site, which lies beneath the new multi-million-pound Bloomberg

headquarters near Mansion House.

The remains are enhanced by light and sound effects, including chants inspired by

ancient graffiti found scrawled on a similar temple in Rome. This recreates what

historians say is “a best guess” about what went on during ceremonies there. An

expert from Museum of London Archaeology Sophie Jackson, an adviser on the

project, said: “London is a Roman city, yet there are few traces of its distant past

that people can experience first-hand. It’s extremely important that a site like this

exists — it is a new and different way of approaching ruins and because it is a

reconstruction we have been allowed to be more creative.”

The remains of the temple were first found when the land was being cleared in

1954. They were removed and installed in a haphazard fashion 100 metres down

the road before Bloomberg took them on as part of the deal to build its

headquarters. About 600 items found during a dig in the area have also gone on

show, including the oldest discovered hand-written document in Britain, etched on a

wooden tablet, and a plaque of a bull. A replica of a relief showing Mithras

sacrificing one of the animals is also on display.

See more at:

BACK TO MENU

Breaking News/4:

The first wine now 6000 years ago

Nicola Davis of the Guardian writes:

A series of excavations in Georgia has uncovered evidence of the world’s earliest

winemaking, in the form of telltale traces within clay pottery dating back to 6,000BC

- suggesting that the practice of making grape wine began hundreds of years earlier

than previously believed.

While there are thousands of cultivars of wine around the world, almost all derive

from just one species of grape, with the Eurasian grape the only species ever

domesticated. Until now, the oldest jars known to have contained wine dated from

7,000 years ago, with six vessels containing the chemical calling cards of the drink

discovered in the Zagros mountains in northern Iran in 1968. The latest find

pushes back the early evidence for the tipple by as much as half a millennium.

The findings suggest the sites were home to the earliest known vintners, besting the

previous record held by the traces of Iranian wine found just 500km away and dated

to 5,400-5,000 BC. Older remnants of winemaking have also been found at the

Jiahu site in China’s Henan province, dating back to 7,000BC, but the fermented

liquid appeared to be a mixture of grapes, hawthorn fruit, rice beer and honey mead.

With their narrow base, the large clay pots used do not stand up easily, suggesting

they might have been half buried in the ground during the winemaking process, as

was the case for the Iranian vessels and which is a traditional practice still used

by some in Georgia.

The find comes after a team of archaeologists and botanists in Georgia joined

forces with researchers in Europe and North America to explore two villages in the

South Caucasus region, about 50km south of the capital Tbilisi. The sites offered a

glimpse into a Neolithic culture characterised by circular mud-brick homes, tools

made of stone and bone and the farming of cattle, pigs, wheat and barley.

Davide Tanasi, of the University of South Florida, said the results of the study were

unquestionable and that the findings were “certainly the example of the oldest pure

grape wine in the world”.

The excavations in Georgia were largely sponsored by the National Wine Agency of

Georgia

“The Georgians are absolutely ecstatic,” said Stephen Batiuk, an archaeologist from

the University of Toronto and one of the study’s co-authors. “They have been saying

for years that they have a very long history of winemaking and this proves it!

BACK TO MENU

Breaking News/5: All that glitters

Laurence Cawley of BBC News reports:

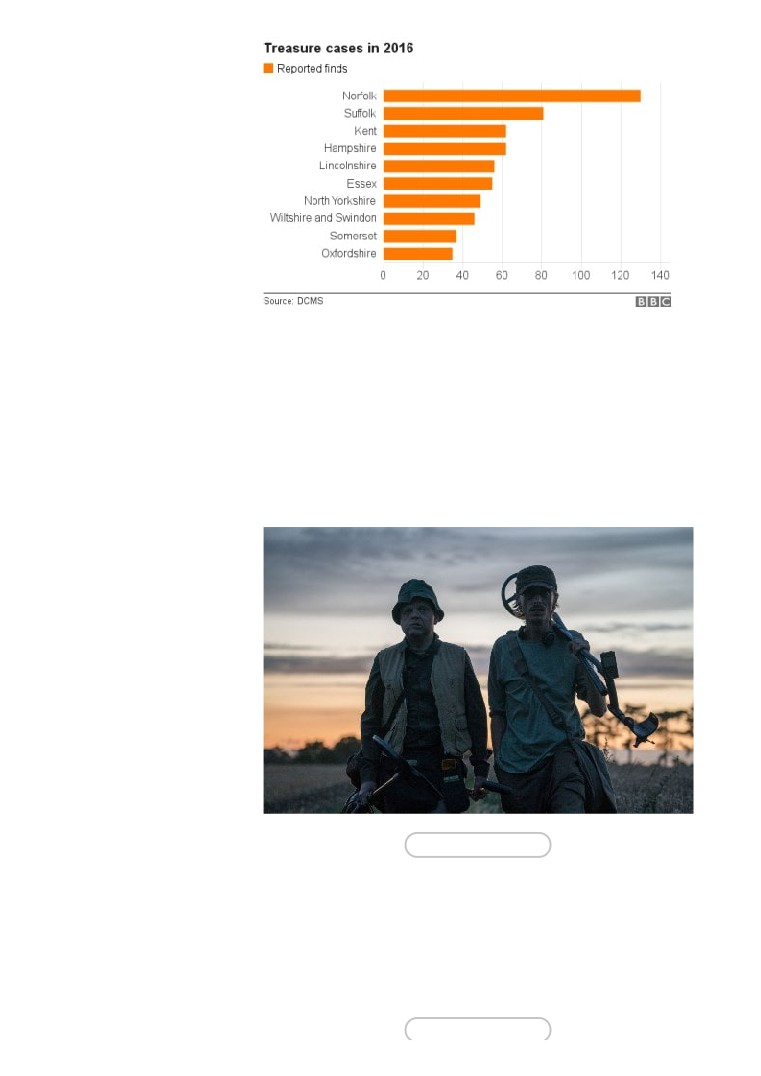

The number of reported annual treasure finds across England has topped more than

1,000 for the first time since records began. But what have been the most intriguing

and important discoveries reported in recent years?

The total number of finds is growing, new figures show. Between 2015 and 2016 the

number of reported treasure finds grew 11% from 966 to 1077. A further 40 were

discovered in Wales and three in Northern Ireland.

So BBC News asked Ian Richardson, the treasure registrar for the Portable

Antiquities Scheme, to name five recent finds that he considers significant. Mr

Richardson tops his list with a Bronze Age torc discovered by detectorists,

people who use metal detectors for a hobby, in Cambridgeshire in late 2015.

Valued at £220,000, the piece is made of 730g of near pure gold.

"It is a bit like a necklace only this is a lot bigger," says Mr Richardson. "It could

have been worn by a pregnant lady or it could have been designed to go around an

animal - we just don't know.

"It is spectacular."

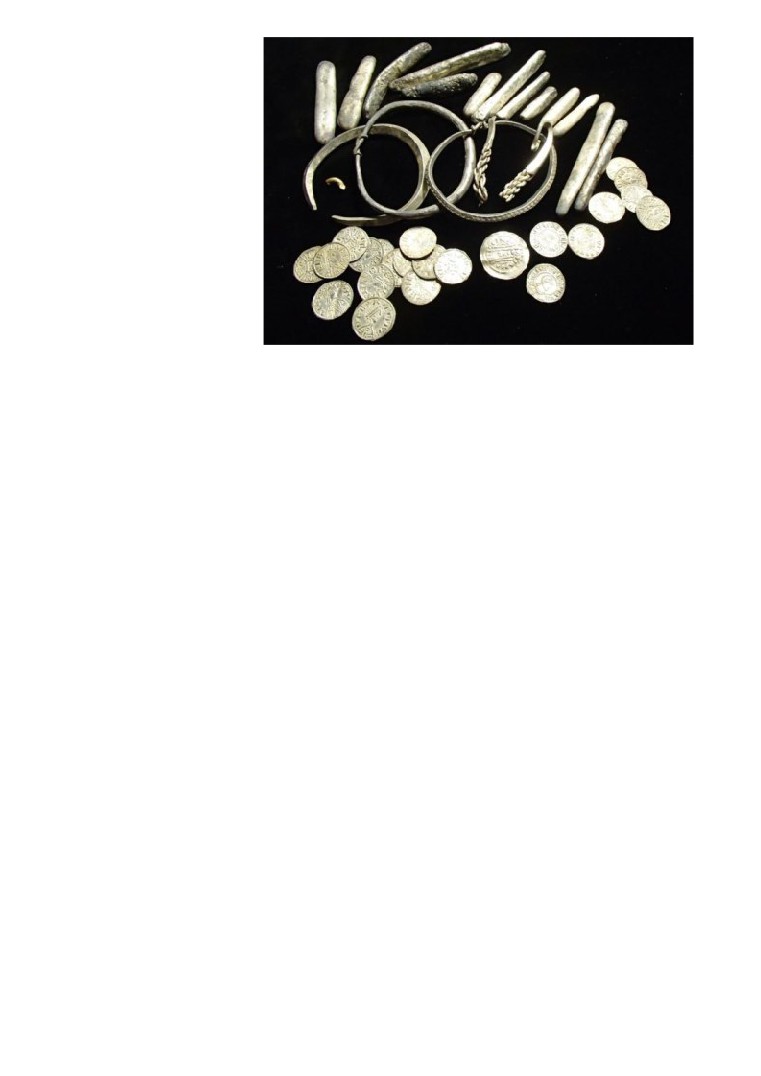

Second on Mr Richardson's list is a Viking hoard of arm rings, coins and silver

ingots unearthed in Oxfordshire in 2015. The hoard was buried near Watlington

around the end of the 870s, in the time of the BBC series The Last Kingdom.

It consists of 186 coins and includes rarities from the time of Alfred The Great of

Wessex, who reigned from 871 to 899, and King Ceolwulf II, who ruled Mercia from

874 to 879.

Archaeologists have called the hoard (above) , discovered by 60-year-old metal

detectorist James Mather, a "nationally significant find".

Classed as treasure because precious metal was found with them, two bowls

uncovered in Hertfordshire are in fact the stars of the show despite being

glassware.

Shattered, but complete, they are now part of a fund-raising bid by the North Herts

Museum which wants to acquire them from the farmer who owns the land where

they were discovered in April 2015.

They are believed to have been made in Alexandria, Egypt.

"As well as some copper alloy vessels there were two glass bowls which were made

using this very special technique and which boast a large number of colours," Mr

Richardson says.

The two bowls, he said, resemble the psychedelic designs of the 1960s despite

dating back to around AD200. Mr Richardson's fifth choice was a medieval silver

pendant which would have once held a tiny religious relic. The relic inside has been

lost, but it is the pendant itself which is the treasure.

The pendant forms the 19th letter of the Greek alphabet - tau - and is made of

separate pieces which join together. Acquired by York Museum, the reliquary

pendant was found in the Selby area in 2015.

About 95% of all treasure finds - defined as any object that is at least 300 years old

when found and with a 10% precious metal content - are made by detectorists.

"There are plenty of things that are absolutely stunning and unique too because they

were made not by machines but by hand," says Mr Richardson. "I often still can't

believe that someone had the skill and time to make some of these things."

Norfolk topped the list for treasure finds with 130 discoveries in 2016, followed by

Suffolk with 81.

The success of detectorists in Norfolk has been put down to how rural it is and

its history of farming, with the soil being turned by ploughs to bring new finds to the

surface.

Julie Shoemark, the finds liaison officer for Norfolk, said the rising number of

reported treasure finds corresponded to a growth in the numbers of metal detecting

clubs.

However that rise, she said, predates the first airing in 2014 of the BBC comedy

BACK TO MENU

Breaking News/6: Most watched TV series by

archaeologists is the BBC comedy series Detectorists

And for Christmas why not buy:

BACK TO MENU

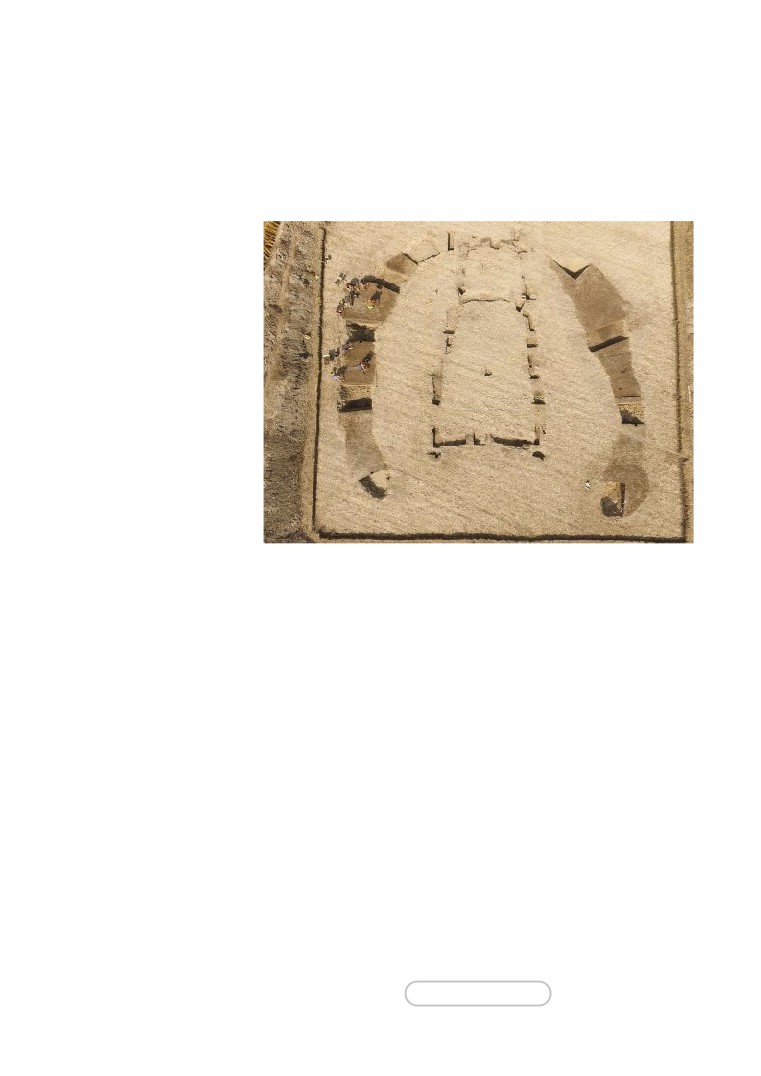

Breaking News/7: Neolithic excitement

Jim Leary Director of Archaeology Field School, University of Reading writes:

The site was excavated as part of the Vale of Pewsey Project, jointly funded by the

University of Reading and the AHRC, in partnership with Historic England and The

Wiltshire Museum. The Vale of Pewsey Project has been the base of the University

of Reading’s Archaeology Field School for the last three years. This year marks the

project’s final field season

This summer, the University of Reading Archaeology Field School excavated one of

the most extraordinary sites we have ever had the pleasure of investigating. The site

is an Early Neolithic long barrow known as “Cat’s Brain” and is likely to date to

around 3,800BC. It lies in the heart of the lush Vale of Pewsey in Wiltshire, UK,

halfway between the iconic monuments of Stonehenge and Avebury.

It has long been assumed that Neolithic long barrows are funerary monuments;

often described as “houses of the dead” due to their similarity in shape to long

houses. But the limited evidence for human remains from many of these

monuments calls this interpretation into question, and suggests that there is still

much to be learnt about them.

In fact, by referring to them as long barrows we may well be missing the main point.

To illustrate this, our excavations at Cat’s Brain (above) failed to find any human

remains, and instead of a tomb they revealed a timber hall, suggesting that it was

very much a “house for the living”. This provides an interesting opportunity to rethink

these famous monuments.

The timber hall at Cat’s Brain was surprisingly large, measuring almost 20 metres

long and ten metres wide at the front. It was built using posts and beam slots, and

some of these timbers were colossal with deep cut foundation trenches, so that it’s

general appearance is of a robust building with space for considerable numbers of

people. The beam slots along the front of the building are substantially deeper than

the others, suggesting that its frontage may have been impressively large,

monumental in fact, and a break halfway along this line indicates the entrance way.

An ancient ‘House Lannister’?

Timber halls such as these are an aspect of the earliest stages of the Neolithic

period in Britain, and there seems little doubt that they were created by early

pioneer Neolithic people. Frequently, they appear to have lasted only two or three

generations before being deliberately destroyed or abandoned. These houses need

not be dwellings, however, and given their size could have acted as large communal

gathering places.

It is worth briefly pausing here and thinking of the image of a house - for the word

“house” is often used as a metaphor for a wider social group (think of the House of

York or Windsor, or - if you’re a Game of Thrones fan like me - House Lannister or

House Tyrell).

In this sense, these large timber halls could symbolise a collective identity, and their

construction a mechanism through which the pioneering community first established

that identity. We may imagine a variety of functions for this building, too, none of

which are mutually exclusive: ceremonial houses or dwellings for the ancestors, for

example, or storehouses for sacred heirlooms.

From this perspective, it is not a huge leap of the imagination to see them as

containing, among other things, human remains. This does not make them funerary

monuments, any more than churches represent funerary monuments to our

community. They were not set apart and divided from buildings for the living, but

represented a combination of the two - houses of the living in a world saturated

with, and inseparable from, the ancestors.

These houses would have been replete with symbolism and meaning, and charged

with spiritual energy; even the process of building them is likely to have taken on

profound significance. In this light, then, it is interesting to note that towards the end

of our excavations this summer, just as we were winding up, we uncovered two

decorated chalk blocks that had been deposited into a posthole during the

construction of the timber hall.

BACK TO MENU

Breaking News/8: Sportsman of the year: Gaius

Appuleius Diocles, a Roman charioteer earned more than

Ronaldo

Cristiano Ronaldo's billing as the world's highest paid sports star has been

challenged by a historian who claims a little known Roman charioteer holds that title

(Tom Kington of the Times writes). Gaius Appuleius Diocles was such a successful

racer at the Circus Maximus in Rome that he earned the modern equivalent of $15

billion in his career, far more than the footballer Ronaldo could dream of, Peter

Struck, a professor of classics at the University of Pennsylvania, claims.

"Diocles is not well known today, but he out earned all of today's superstars," said

Professor Struck, who found a monument to Diocles built by his fellow charioteers

that listed his total earnings as 35,863,120 sesterces.

Diocles was from Portugal, like Ronaldo, and arrived in Rome to make his name.

"He was probably illiterate and this was his best shot at making a life," Professor

Struck said. "To survive you needed physical strength and a mindless courage.

Death was common, which is what the crowd lusted after."

Diocles survived 24 years in the arena, was known for fast, final sprints and earned

the equivalent of $625 million a year — six times what Ronaldo was paid last year.

On his monument, erected in 146 AD, his admirers wrote Diocles retired at the age

of "42 years, 7 months, and 23 days" as "champion of all charioteers".

His earnings were enough to provide grain for the city of Rome for a year or to pay

all Roman soldiers for about two months when the empire was at its height,

Professor Struck calculated. He compared that with the US armed forces' wage bill

to arrive at the figure of $15 billion.

"There is no way of converting ancient amounts to modern money unless you

calculate how much something cost then to how much it costs now,"

Mary Beard, professor of history at Cambridge, said. "Struck's method is sensible."

BACK TO MENU

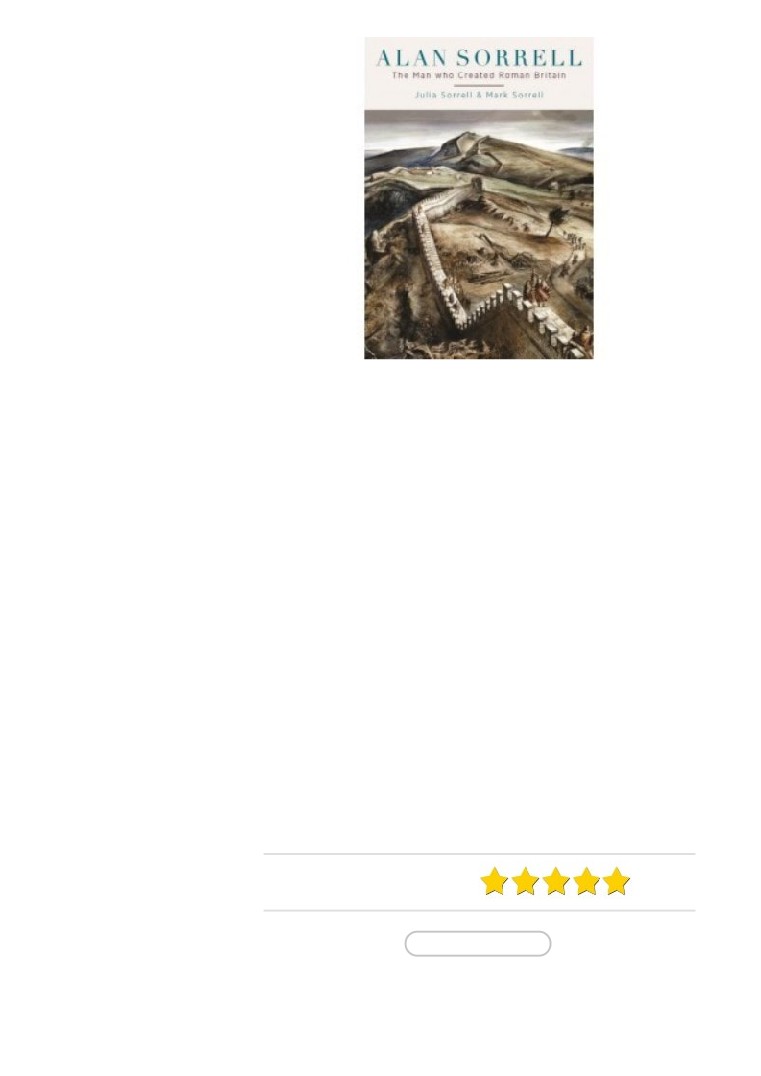

Books for Christmas 1/ Alan Sorrell:

The man who created Roman Britain

Authors Julie and Mark Sorrell and published by Oxbow Books

Alan Sorrell’s archaeological reconstruction drawings and paintings remain some of

the best, most accurate and most accomplished paintings of their genre that

continue to inform our understanding and appreciation of historic buildings and

monuments in Europe, the Near East and throughout the UK.

His famously stormy and smoky townscapes, especially those of Roman Britain,

were based on meticulous attention to detail borne of detailed research in

collaboration with archaeologists such as Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Sir Cyril Fox and Sir

Barry Cunliffe, who excavated and recorded his subjects of interest.

Many of his reconstructions were commissioned to accompany visitor information

and guidebooks at historic sites and monuments where they continue to be

displayed. But archaeological subjects were not his only interest. His output was

prodigious: he painted murals, portraits, imaginative and romantic scenes and was

an accomplished war artist, serving in the RAF in World War II.

In this affectionate but objective account, Sorrell’s children, both also artists, present

a brief pictorial biography followed by more detailed descriptions of the genesis,

research and production of illustrations that demonstrate the artist’s integrity and

vision, based largely on family archives and illustrated throughout with Sorrell’s own

works.

So influential were Sorrell’s images of Roman towns such as London, Colchester,

Wroxeter, St Albans and Bath, buildings such as the Heathrow temple and the forts

of Hadrian’s Wall, that he became known as the man who invented Roman Britain.

Rating: 5 stars

BACK TO MENU

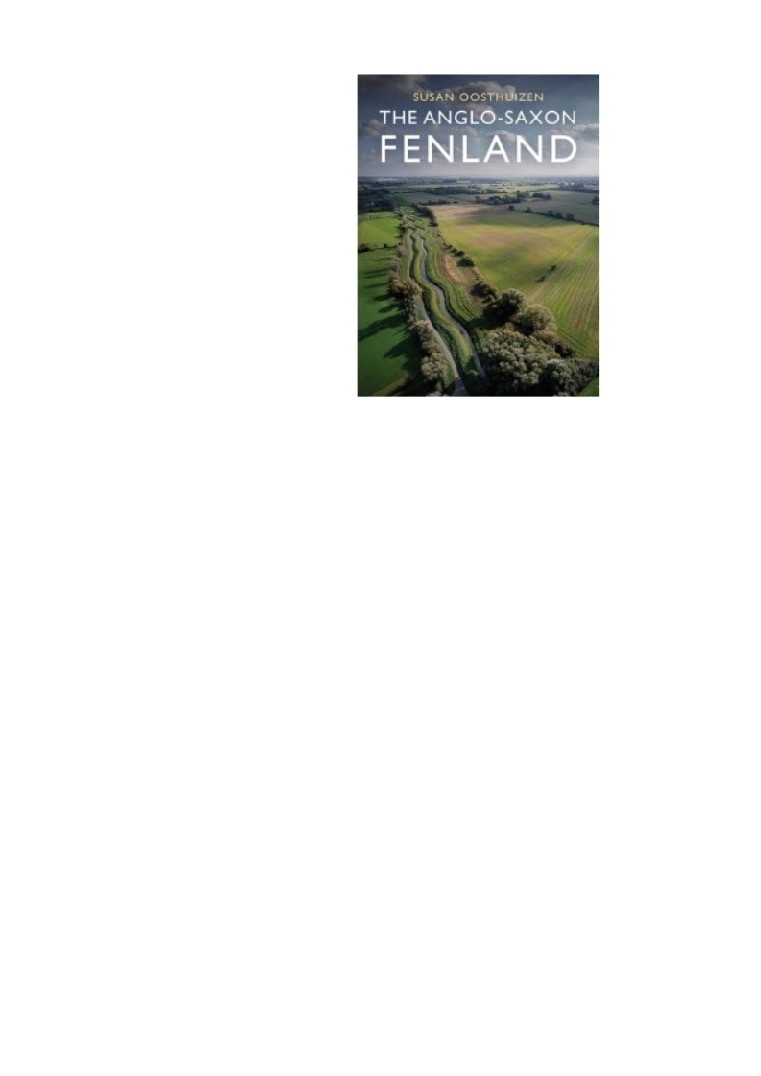

Books for Christmas 2/

The Anglo-Saxon Fenland by Susan Oosthuizen

Archaeologies and histories of the fens of eastern England, continue to suggest,

explicitly or by implication, that the early medieval fenland was dominated by the

activities of north-west European colonists in a largely empty landscape. Using

existing and new evidence and arguments, this new interdisciplinary history of the

Anglo-Saxon fenland offers another interpretation. The fen islands and the silt fens

show a degree of occupation unexpected a few decades ago. Dense Romano-

British settlement appears to have been followed by consistent early medieval

occupation on every island in the peat fens and across the silt fens, despite the

impact of climatic change. The inhabitants of the region were organised within

territorial groups in a complicated, almost certainly dynamic, hierarchy of

subordinate and dominant polities, principalities and kingdoms. Their prosperous

livelihoods were based on careful collective control, exploitation and management of

the vast natural water-meadows on which their herds of cattle grazed. This was a

society whose origins could be found in prehistoric Britain, and which had evolved

through the period of Roman control and into the post-imperial decades and

centuries that followed. The rich and complex history of the development of the

region shows, it is argued, a traditional social order evolving, adapting and

innovating in response to changing times.

Review

“…offers a fresh perspective on a relatively poorly defined period, usefully

questioning established views, long taken for granted, and generating a new set of

carefully argued hypotheses that should focus attention for a new generation of

researchers.” (Bob Sylvester Medieval Settlement Research Group)

“This important and thoroughly researched book makes a very good case for long-

term continuity in the specialised management needed for the Fenland.” (David Bird

British Archaeology Review, January/February 2018)

About the Author

Susan Oosthuizen is reader in medieval archaeology in the Department of

Continuing Education at the University of Cambridge. She teaches in landscape and

field archaeology, including garden archaeology, with a special interest in Anglo-

Saxon and medieval landscapes, the archaeology of the Doomsday Book and in the

development of research skills

Rating: 5 stars

BACK TO MENU

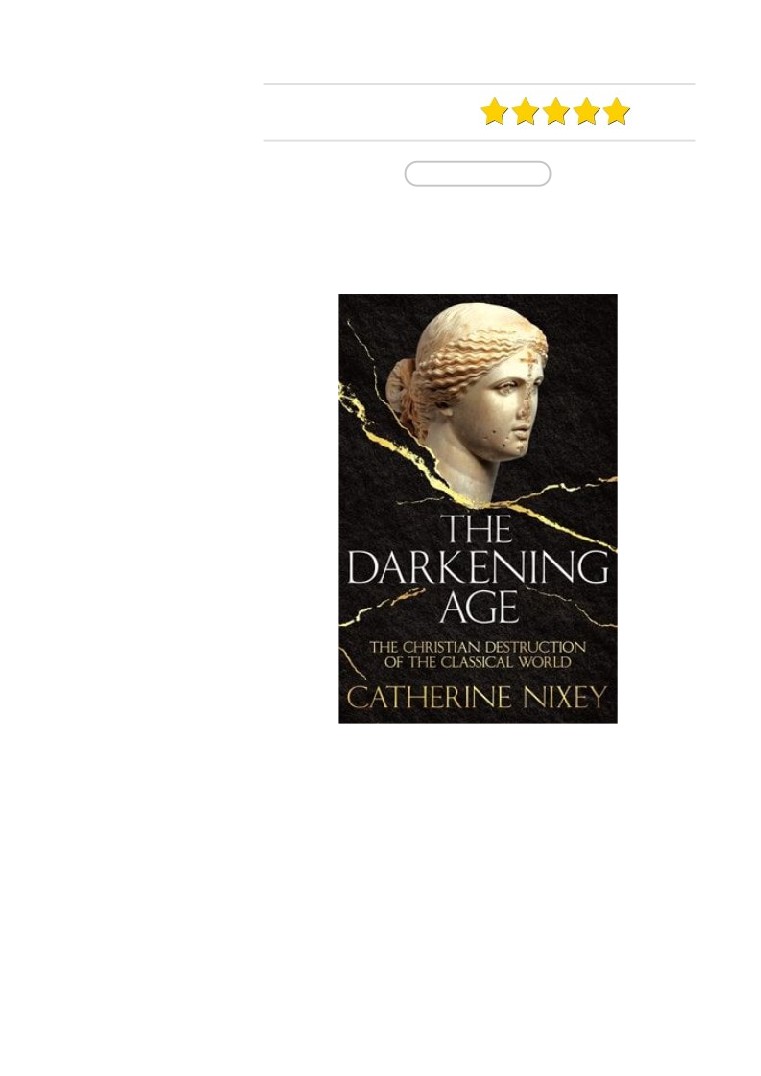

Books for Christmas 3/

The Darkening Age by Catherine Nixey

Gerard DeGroot of the London Times writes:

About AD250, the Roman Emperor Decius declared that Christians who refused to

sacrifice to the gods would be killed. Steadfast in their beliefs, seven Christians from

Ephesus hid in a cave, where they fervently prayed to their one true God. Decius,

angry at their defiance, had the cave sealed.

Some 360 years later, masons quarrying for stone opened the cave. Rome had

meanwhile become a Christian empire. The seven rebels awoke from their slumber,

assuming they had slept just one night. Feeling understandably hungry, one of them

went looking for food. He found Ephesus miraculously transformed into a Christian

city. God had answered their prayers.

In AD312 the Emperor Constantine declared himself a follower of Christ. Historians

have, ever since, seen this conversion as progress. Rome abandoned brutal

paganism and took up civilised Christianity.

The people rejoiced. Not so, argues Catherine Nixey.

The accepted narrative, Nixey believes, is a lot like that mythical Ephesus story — a

miraculous overnight transformation. In fact, a lot of nasty stuff happened while

those men were sleeping. The transition to Christianity was anything but smooth. It

wasn't even progress.

"And ye shall overthrow their altars, and break their pillars, and... hew down the

graven images of their gods." So go the words of Deuteronomy, instruction that

Christians took seriously. They pulled down pillars, smashed altars and hewed

statues everywhere. The righteous sang, laughed and danced while they trampled

an ancient culture. Desecration was "a thoroughly enjoyable way to spend an

afternoon",

writes Nixey, an arts journalist at The Times. If you have wondered why so many

classical statues are missing heads, arms, noses and genitalia, now you know.

Historians have given those desecrators an easy ride. They are usually described

as pious or zealous, not as thugs or thieves.

Victors, you see, write history. When a monotheistic religion replaces one that

sacrifices goats to its gods, that's described as progress. Yet triumph, in this case,

meant not only victory, but annihilation.

This book uncovers what was lost when Christianity won. It "unashamedly mourns

the largest destruction of art that human history has ever seen".

In the 4th century the most magnificent building in the world was not the Parthenon

or the Colosseum.

It was the Temple of Serapis in Alexandria, with its interior walls of gold and silver.

The temple housed the world's first public library, with about 700,000 books.

It had withstood earthquakes, but it could not withstand Christian fanatics, who

attacked in AD392.

They pulled down columns, decapitated the enormous statue of Serapis, took away

precious metals and burnt everything else. "One can achieve a great deal by the

blunt weapons of ignorance and stupidity,"

Nixey writes. Did these desecrators, she wonders, pause to admire the beauty they

destroyed?

Christians attacked not only buildings and sculptures. Ideas were likewise

destroyed. Before Constantine's conversion, the intellectual was fashionable in

Rome. One superstar mind was the dissector Galen, who carried out public

eviscerations of pigs and apes.

The Darkening Age is a delightful book about destruction and despair. Nixey

combines the authority of a serious academic with the expressive style of a good

journalist.

She's not afraid to throw in the odd joke amid sombre tales of desecration. With

considerable courage, she challenges the wisdom of history and manages to

prevail.

Comfortable assumptions about Christian progress come tumbling down.

Speaking of progress, a lot of that fanaticism looks awfully familiar. The abbot

Shenoute, who set out to "obliterate the tyranny of joy", reminded me of Pol Pot.

The destruction of pagan temples by Christians (right) is not unlike what Islamic

State gets up to today. And as for the demonization of science, well. You know

Rating: 4 stars

BACK TO MENU

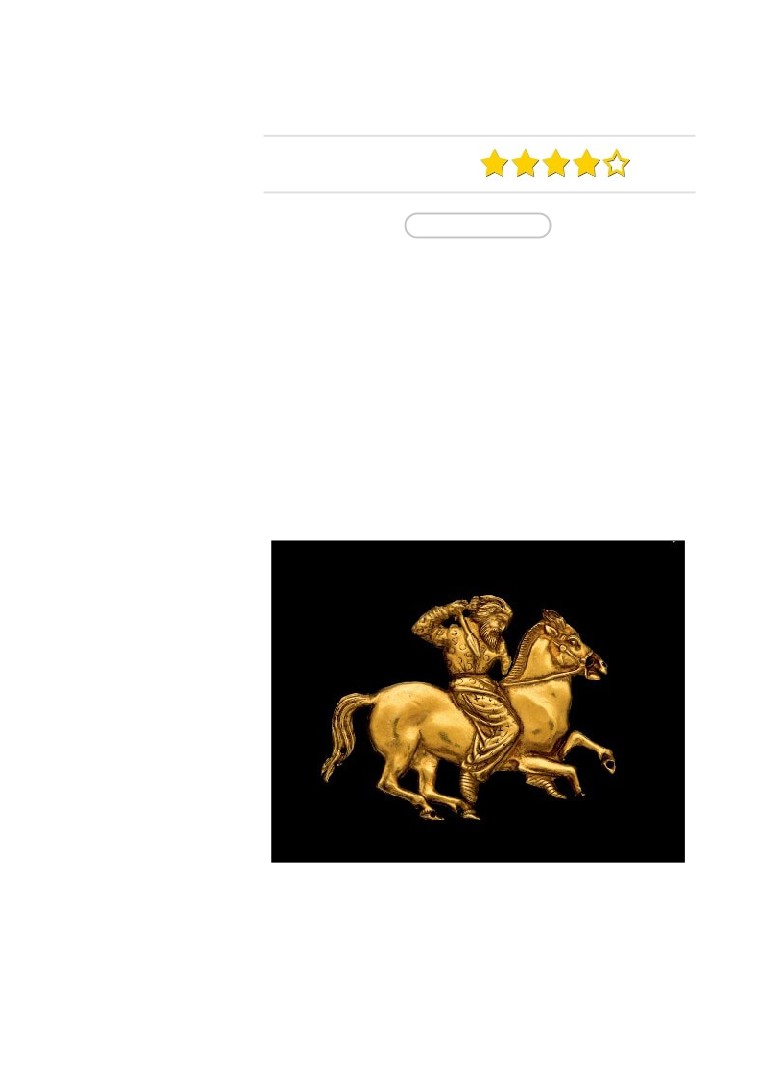

Must see exhibitions/1

Scythians: warriors of ancient Siberia

14 September 2017 - 14 January 2018, Room 30, Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery.

£16.50, Members/under 16s free

2,500 years ago groups of formidable warriors roamed the vast open plains of

Siberia. Feared, loathed, admired - but over time forgotten... Until now.

This major exhibition explores the story of the Scythians - nomadic tribes and

masters of mounted warfare, who flourished between 900 and 200 BC. Their

lifestyle and ferocity has echoed through the ages. Other groups from the Huns to

the Mongols have followed in the Scythians' footsteps

- and they have even

influenced the portrayal of the Dothraki in Game of Thrones. The Scythians'

encounters with the Greeks, Assyrians and Persians were written into history but for

centuries all trace of their culture was lost - buried beneath the ice.

Discoveries of ancient tombs have unearthed a wealth of Scythian treasures.

Amazingly preserved in the permafrost, clothes and fabrics, food and weapons,

spectacular gold jewellery - even mummified warriors and horses - are revealing

the truth about these people’s lives. These incredible finds tell the story of a rich

civilisation, which eventually stretched from its homeland in Siberia as far as the

Black Sea and even the edge of China.

Many of the objects in this stunning exhibition are on loan from the State Hermitage

Museum in St Petersburg. Scientists and archaeologists are continuing to discover

more about these warriors and bring their stories back to life.

Explore their lost world and discover the splendour, the sophistication and the sheer

power of the mysterious Scythians.

BACK TO MENU

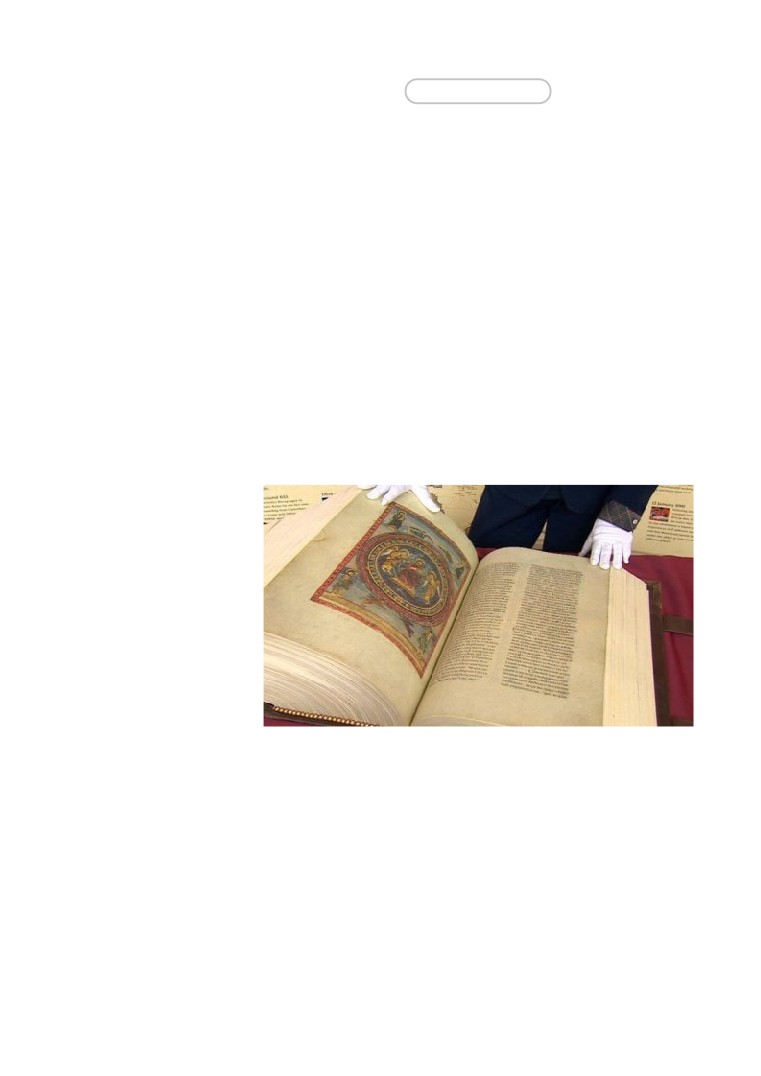

Must see exhibitions/2

Anglo-Saxon bible returns to England

after 1,302 years

British Library:

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms

(19 October 2018 - 19 February 2019)

Mark Brown Arts correspondent of the London Times writes:

The oldest complete Latin bible in existence, which is one of the greatest Anglo-

Saxon treasures, is returning to England after 1,302 years.

The Codex Amiatinus is a beautiful and gigantic bible produced in Northumbria by

monks in 716 which, on its completion, was taken to Italy as a gift for Pope Gregory

II.

The British Library announced it had secured its loan from the Laurentian Library in

Florence in 2018 for a landmark exhibition on the history, art, literature and culture of

Anglo-Saxon England.

Claire Breay, the library's head of medieval manuscripts, said: "It is the earliest

surviving complete bible in Latin. It has never been back to Britain in 1,302 years but

it is coming back for this exhibition. It is very exciting."

The bible is considered one of the best surviving treasures from Anglo- Saxon

England but is not widely known outside academic circles.

"I've been to see it once and it is unbelievable," said Breay. "Even though I'd read

about it and seen photographs, when you actually see the real thing... it is a

wonderful, unbelievably impressive manuscript."

Part of its power is its size. Nearly half a metre high and weighing more than 75

pounds, over a thousand animal skins were needed to make its parchment.

It was one of three commissioned by Ceolfrith, the abbot of Wearmouth- Jarrow

monastery, and was a mammoth undertaking, said Breay. Of the others, one is lost

and another exists in small fragments at the British Library.

Ceolfrith was part of a team of monks who took the bible to Italy, though he never

got to see it arrive as he died on the journey, in Burgundy, France.

It was kept at the monastery in San Salvatore, Tuscany, before arriving at the

Laurentian Library in the late 18th century, where it has remained one of its greatest

treasures. The Codex Amiatinus will be displayed alongside the Lindisfarne Gospels

and other illuminated manuscripts, including the Benedictional of St Ethelwold,

which includes the earliest surviving image of the three wise men wearing crowns.

Breay said the autumn exhibition would shine light on the sophistication of Anglo-

Saxon culture, a period often dismissed as the Dark Ages.

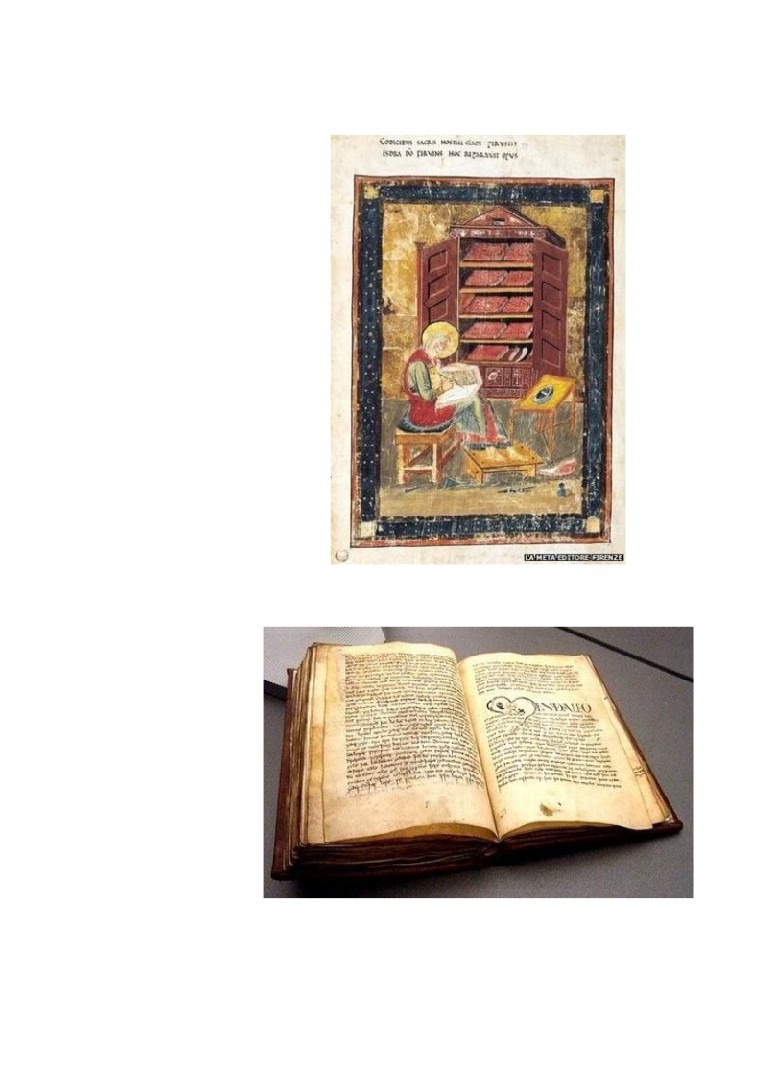

This plate (below) from the Codex Amiatinus depicts Ezra, the ancient scribe and

priest.

Another coup will be the loan, also from Italy, of an important manuscript of Old

English poetry known as the Vercelli Book. Dating from the 10th century (above), it

returns to Britain for the first time and is being lent by the Biblioteca Capitolare in

Vercelli.

These Highlights from the British Library’s outstanding collection of Anglo-Saxon

manuscripts will be presented alongside a large number of exceptional loans.

The Codex Amiatinus, one of three giant single-volume Bibles made at the

monastery at Wearmouth-Jarrow in the north-east of England in the early eighth

century and taken to Italy as a gift for the Pope in 716, will be returning to England

for the first time in more than

1300 years, on loan from Biblioteca Medicea

Laurenziana in Florence. It will be displayed with the St Cuthbert Gospel, also

made at Wearmouth-Jarrow around the same time, and acquired by the British

Library in 2012.

We can also reveal that we will be displaying a number of major objects from the

Staffordshire Hoard, found in 2009, including the pectoral cross and the inscribed

gilded strip, on loan from Birmingham and Stoke-on-Trent City Councils.

Bringing together the four principal manuscripts of Old English poetry for the first

time, the British Library’s unique manuscript of Beowulf will be displayed alongside

the Vercelli Book on loan from the Biblioteca Capitolare in Vercelli, the Exeter

Book on loan from Exeter Cathedral Library, and the Junius Manuscript on loan

from the Bodleian Library.

BACK TO MENU

Background reading:

Beowulf in Kent by Dr Paul Wilkinson

Gary Budden writes:

It’s a compelling thought.; the monster Grendel inhabiting the bleak marshlands of

the Isle of Harty (part of what we now call Sheppey), just over the water from the

town of Faversham, separated from the mainland by The Swale. These islands tend

to overfeed the imagination; lost tribes can dwell there, grisly remains, evolutionary

dead ends, the sons of Cain.

Sheppey, and the other small islands that appear as odd unmarked blanks of green

on Google Maps, hold dark histories. Deadmans Island and Burnt Wick Island, so

close to home and practically unknown, are borderline inaccessible. They hold the

mass graves of Napoleonic French prisoners who died on the prison hulks (you’ll

know them from Great Expectations) and their bones now rise from the silt. Walk the

Hollow Shore between Faversham and Whitstable, look out over to the island

across the Swale, no one else around and the wind stinging the eyes. It’s easy to

feel Anglo-Saxon in such a place.

More than anything we want the monsters to be there.

I remember looking at the Beowulf manuscript in the British Library for a long time

the first time I saw it. It exerted a pull over me that beat any Chinese scroll or Lewis

Carroll diary. I read the Heaney translation, discovered American writer John

Gardner’s monster-perspective novel, Grendel, as part of the Fantasy Masterworks

series (terrible cover). I even watched the film written by Neil Gaiman and with Ray

Winstone as our founding English hero, getting entangled with a version of

Grendel’s mother who was rather sexier than I’d always imagined.

When I started researching the areas of north east Kent where I grew up, especially

the stretch of coast along the Thames estuary, I came across a curious piece of

information on the Faversham website:

Nearly ten years ago Dr Paul Wilkinson, a Swale archaeologist, and Faversham

journalist and business woman Griselda Mussett contributed a Faversham Paper

which makes a strong, and believable, claim based on topographical and oral and

written folk history that the Beowulf legend had its origins among place names that

were commonplace and are still to be seen around the Faversham area.

I tracked down the papers via the Faversham society and duly received them in the

post. I felt like I was falling down a rabbit hole of crackpot theories and dubious

speculation. If I’m honest, I wasn’t much interested in the truth of any of the theories.

The story appealed. Ray Winstone’s cockney accent suddenly made a sort-of

sense. Beowulf as the ex-Londoner moved out to the estuary.

Paul Wilkinson’s colour booklet, Beowulf on the Island of Harty in Kent proudly

proclaims AS SEEN ON TV in its bottom right corner, and features the Sutton Hoo

mask as its cover, which already seems to be muddying the issue. Near the

beginning, he does concede what we’re really dealing with here is mythology, not

archaeology or science:

Mythology, on the other hand, is concerned above all with what happened in the

beginning. It’s signature is ‘Once upon a time’ and our English beginning could be a

small island called Harty just off, but belonging to, the port of Faversham in Kent.

In this Kentish interpretation of the tale, Harty becomes Heorot (Hrothgar’s hall).

Heorot sits at the heart of a large Lathe, or administrative area, the schrawynghop,

an area ‘inhabited by one or several supernatural malignant beings’.

Hop means a piece of enclosed land in the middle of marshes, or wasteland.

Wilkinson cites sources who claim that the only linguistic clues we can glean from

the Old English is from the text of Beowulf itself, where the monsters’ lairs are called

fenhopu and morhopu - marsh retreats. ‘Schraw’ approximates to many words from

old Germanic dialects meaning dwarf, goblin, devil, the villain, and so on. Here lies

the problem of language; its imperfect nature, its multitude of meanings and

interpretations, allowing us, literally, to read what we want into it.

The theory even goes as to suggest that Beowulf was buried under Nagden mound

(a possible artificial hill that was destroyed in 1953 by men contracted to rebuild the

sea wall between Faversham and Seasalter, after the great North Sea flood.),

though by this point the theory has fallen more into wishful thinking and a lot of

‘maybes’ rather than anything that could approximate a credible argument. In my

fictional landscape, Grendel and his mother fit in well with the bodies of those dead

Frenchman, the prisons across the water on Sheppey, the bleak marshes, the

boxing hares and the black curlews of my own fictions.

I know these tidal flats and malignant bogs were dry land once, attached to the

Doggerland landmass that connected what was to become Britain to the coasts of

Germany and Denmark. My mind already is flowing with ideas, stories of the last

remaining malignant supernatural beings that inhabited Doggerland making a last

stand in the Kentish marshes. Wiped out by Ray Winstone. Grendel having his arm

pulled from its socket on the demon marsh in the Thames estuary. A dragon above

Faversham.

It’s a good idea for a story, right?

Maybe that’s enough.

The Andrews Dury map dated 1769 of Harty shows Warden and Lands End both

places of importance in the Beowulf saga

BACK TO MENU

And finally - Christmas in Kent with Paul Wilkinson a

long, long time ago

Paul Wilkinson writing in the Kentish Times:

“One bright sunlit day in early December I was walking with a group of

archaeologists in a field just outside Faversham and close to Brenley Corner

roundabout. In this field a classical Roman temple was supposed to have been

uncovered many years ago. I stooped down to pick up an object out of the mud and

as I cleaned it I could see it was a broken pottery figurine of the pagan god Saturn

whose festival of light coincided with the winter solstice usually on December 22nd

or 23rd.

The Romans loved a good party and feasting continued to one of the most important

days in the Roman calendar, December 25th, the Sol Invictus, the ‘Birthday of the

Unconquerable Sun’, the whole festival being called ‘Saturnalia’, a time of feasting,

role reversal, gift giving and gambling.

I looked up and a group of Romans were smiling at me. Beyond I could see not one,

but two classical temples, both in disrepair and boarded up. ‘No good holding on to

that’, the leader said.

‘The old religion has been dead for years, we are now

Christians, it’s the official religion of the Roman Empire’. ‘Come join us, we are going

to celebrate the birth of Christ and it is called Christmas- same date as the old

religion so us ‘pagi’ don’t get confused!’

I asked where they were going and they told me the Imperial Post coach stopped

here and we had a group ticket. I joined them and travelled for about two hours on

the great Roman road alighting at a grand Roman villa overlooking a wide river.

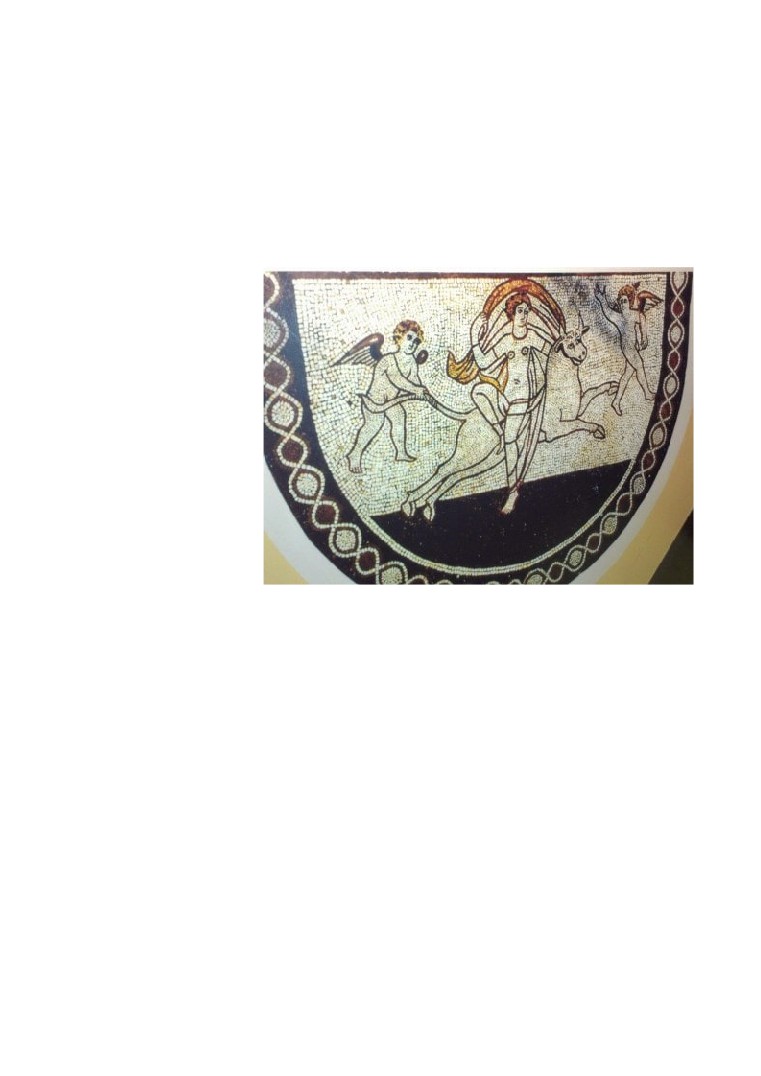

‘Come inside’ they said and we entered a dining room with a huge floor mosaic

depicting Europa sitting on a bull which in fact was Jupiter in disguise, Above the

mosaic were two lines of Latin text. ‘Read closely’ my companion Avitus said, ‘this is

the secret key to the church’. I suddenly saw what he meant for in the second line

was concealed the word ‘IESVS’ (Jesus), and both lines of text started with ‘I’ and

ended with

‘S’ . Avitus explained that for many years Christians had been

persecuted by the Roman state and Christians worshipped in secret.

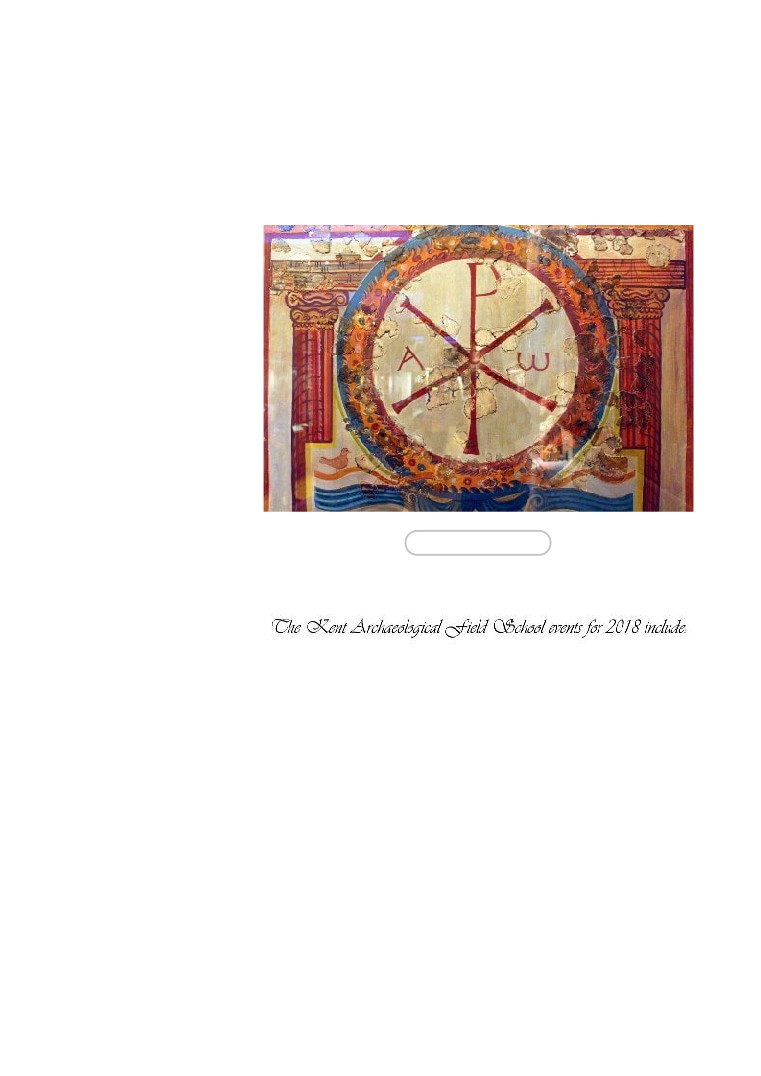

We entered the house church and the wall paintings were amazing, they showed on

the west wall a fresco of a roofed colonnade upon a flowered dado, with Christians

standing between the columns attired in the rich beaded robes of the late fourth

century, and with their arms outstretched in the attitude of prayer. In the middle was

a huge Chi-Rho monogram, the monogram red upon a white background,

surrounded by a large wreath of flowers and fruit with the Alpha and Omega

occupying their usual places between the spreading arms of the Chi.

Avitus explained, ‘the Chi-Rho symbol was introduced by the Emperor Constantine

on the shields of his legions. It denotes the first two letters of the Greek word ‘Christ’

which comes from the Hebrew ‘Christos’ meaning ‘anointed’. The two Greek letters

Alpha and Omega are the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet and symbolise

that Christ is the beginning and end of all things’.

As they turned to pray on December 25th AD 379 at a Roman villa church in Kent I

shook their hands and wished them all a good Christmas both then and through all

time.

BACK TO MENU

We will be back in Oplontis in the first three weeks in June 2018 for another

season of excavation and anyone can join our team. The only criteria is that you

are a member of the Kent Archaeological Field School www.kafs.co.uk and that you

have some experience or enthusiasm for Roman archaeology, Italian food and

Italian sunshine! See also the website for the project at www.oplontisproject.org.

The weekly fee is £175. Please note food, accommodation, insurance, and travel

are not included.

Flights to Naples are probably cheapest with EasyJet. To get to Pompeii take a bus

from the Naples airport to the railway station and then the local train to Pompeii.

Hotels are about 50eu for a room per night.

We are staying at are the Motel Villa dei Misteri and the Hotel degli Amici.

The dates are from 28th May to 15th June 2018

Transport to Oplontis from Pompeii is not provided but most of the group use the

local train (one stop). Please note it can be hot so bring sun cream and insect

07885 700 112. We will meet up at 8am every Monday morning of the dig to start

the new week. This may be the last year so grasp the opportunity! Places are

limited.

Paul Wilkinson

BACK TO MENU

Courses at the Kent Archaeological Field School for 2018

will include:

Field Walking and Map Analysis Easter Good Friday March 30th & Saturday

31st March

Field work at its most basic involves walking across the landscape recording

features seen on the ground. On this weekend course we are concerned with

recognising and recording artefacts found within the plough soil. These include flint

tools, Roman building material, pottery, glass and metal artefacts. One of the uses

of field walking is to build up a database for large-scale regional archaeological

surveys. We will consider the importance of regressive map analysis as part of this

procedure. The course will cover:

1. Strategies and procedures,

2. Standard and non-standard line walking, grid walking,

3. Pottery distribution, identifying pottery and building ceramics.

We will be in the field in the afternoons so suitable clothing will be necessary.

Cost £50 if membership is taken out at the time of booking. For non-members the

cost will be £75.

May Bank Holiday May 28th, 29th: Archaeological test pitting on the site of a

recently discovered Roman Villa (or water mill) at Wye in Kent

On this weekend course we shall look at the ways in which archaeological sites are

discovered and excavated and how different types of finds are studied to reveal the

lives of former peoples. Subjects discussed will include aerial photography,

regressive map analysis, HER data, and artefact identification. This course will be

especially useful for those new to archaeology, as well as those considering

studying the subject further. In the afternoons we will participate in an archaeological

investigation on a Roman building under expert tuition.

Cost is £50 if membership is taken out at the time of booking. For non-members the

cost will be £75.

May 28th to June 15th 2018 excavating at 'Villa B' at Oplontis next to Pompeii

in Italy

We will be spending three weeks in association with the University of Texas

investigating the Roman Emporium (Villa B) at Oplontis next to Pompeii. The site

offers a unique opportunity to dig on iconic World Heritage Site in Italy and is a

wonderful once in a lifetime opportunity. Cost is £175 a week which does not include

board or food but details of where to stay are available (Camping is 12EU a day and

the adjacent hotel 50EU or Airbnb).

Frescoes from Oplontis ‘Villa B’

July 30th to August 9th 2018. The final investigation of a substantial Roman

Building at Faversham in Kent

Two weeks investigating a substantial Roman building to find out its form and

function. This is an important Roman building and part of a larger Roman villa

complex which may have its own harbour. One of the research questions we will be

tackling is the buildings marine association with the nearby tidal waterway. Cost for

the day £10 (Members free).

August 6th to August 10th 2018 Training Week for Students on a Roman

Building at Faversham in Kent It is essential that anyone thinking of digging on an

archaeological site is trained in the procedures used in professional archaeology. Dr

Paul Wilkinson, author of the best selling "Archaeology" book and Director of the

dig, will spend five days explaining to participants the methods used in modern

archaeology. A typical training day will be classroom theory in the morning (at the

Field School) followed by excavation at a Roman villa near Faversham.

Topics taught each day are:

Monday 6th August: Why dig? Tuesday 7th August: Excavation Techniques.

Wednesday 8th August: Site Survey. Thursday

9th August: Archaeological

Recording. Friday 10th August: Pottery identification. Saturday and Sunday (free)

digging with the team

A free PDF copy of "Archaeology" 3rd Edition will be given to participants. Cost for

the course is £100 if membership is taken out at the time of booking plus a

Certificate of Attendance. The day starts at 10am and finishes at 4.30pm. For

directions to the Field School see 'Where ' on this website. For camping nearby see

September

10th to

21th

2018. Investigation of Prehistoric features at

Hollingbourne in Kent

An opportunity to participate in excavating and recording prehistoric features in the

landscape. The two weeks are to be spent in excavating Bronze and Iron Age

features inside a small prehistoric homestead on the North Downs that was located

with aerial photography and field survey. Cost is £10 a day for non-members,

members free.

Hollingbourne 2017

BACK TO MENU

The Kent Archaeological Field School, School Farm Oast,

Graveney Road, Faversham, Kent ME13 8UP

Director Dr Paul Wilkinson MCIfA

KAFS BOOKING FORM

You can download the KAFS booking form for all of our forthcoming courses directly

from our website, or by clicking here

KAFS MEMBERSHIP FORM

You can download the KAFS membership form directly from our website, or by

BACK TO MENU

If you would like to be removed from the KAFS mailing list please do so by clicking here